As Brett Goldstein sat down on The Drew Barrymore Show, pandemic earnestness in his eyes, he ventured into territory more personal than usual. People remember Goldstein for his dry wit as Roy Kent on Ted Lasso, for scripts he’s penned, for his unexpected vulnerabilities.

That evening, he spoke about something that sounded almost surreal: a childhood memory so vivid that he said E.T. the Extra‑Terrestrial left him with symptoms he now likens to PTSD, starting as early as age three.

The statement stunned the audience, and left many reflecting on how deeply early impressions, even from films, can impact a child’s psyche.

He described how, at three, he must have caught E.T. on television or in a family viewing, though he doesn’t remember exactly when. What he does remember, he said, is the feeling of terror when the alien creature began to be pursued, the looming threat from the government in the movie, the sense that this being—innocent, wanting to go home—was being hunted.

For a toddler already sensitive to big noises or shadows, Goldstein said, these scenes didn’t just entertain—they unsettled. “I woke up crying,” he recalled. “Sometimes when my parents left me in the dark, I thought I’d see that government spaceship through the door.” His voice quavering, he admitted that the movie stayed with him longer than any toy or lullaby did.

By Goldstein’s account, these early imaginative fears didn’t necessarily cripple him, but they laid a foundation of anxiety. Loud noises, unknown darkness, separations—they triggered echoes of those movie scenes.

For years, he thought his reactions were just part of being a dramatic kid. It was only later, after reading about trauma, watching other people share similar early memories, that he could put a name to what he’d felt: post‑traumatic stress symptoms.

He clarified that he doesn’t believe the film itself caused PTSD in the clinical sense, and that other factors likely contributed. But the images, he said, “etched themselves into my brain” in ways he didn’t escape.

Goldstein’s revelation sparked a broader conversation on the show about how childhood is shaped by what we consume—what movies we watch, what stories we hear, what shadows flicker in our imagination just before sleep.

Drew Barrymore, current guest host, shared her own childhood movie experiences, acknowledging how some films scared her, but also how she saw them as rites of passage.

The two spoke about how many parents now try to gauge what media is appropriate for their kids, sometimes perhaps underestimating how vivid a young child’s imagination can be.

Mental health experts watching after the show weighed in. Many noted: what Goldstein described is not uncommon. Children exposed to frightening media without the scaffolding of explanation—without someone there to hold their hand and contextualize—can find their fears slipping into longer‑lasting anxieties.

While the diagnostic line for PTSD is careful and specific, the broad experience of lingering fear, nightmares, separation anxiety or hypervigilance can stem from early frightening experiences—media included.

One psychologist commenting to a media outlet said that in many cases, children don’t need to have experienced large traumas in the real world to carry scars—in some cases, fictional events amplified by imagination leave surprisingly real emotional marks.

Goldstein also spoke with humility: he was not trying to indict E.T. or Spielberg or anyone else. He emphasized his admiration for the film—that it’s a classic, that it moved people, that it still means a lot. What he was willing to consider, though, is how a film that shapes public culture can interact with a young mind in unexpected ways.

He discussed how parents in his childhood didn’t necessarily think twice about what their toddler was seeing on screen. It was not uncommon, he said, for him or his siblings to watch films that were beyond what they later understood, simply because there wasn’t much media awareness or content warning at the time.

The conversation turned to how Goldstein has tried to work through this over the years—through therapy, through art, through laughter. He credits comedy as a kind of healing: finding humor in fear, or making absurd what once triggered anxiety.

He also said that acting helps him channel those early intense emotions into controlled spaces. When playing a scene, he can draw on something similar and lean into it, but also step away from it. It’s a form of emotional muscle-building.

Audience reactions were mixed: some sympathized immediately, relating similar childhood fears, while others pushed back, wondering whether attributing childhood fear to a film was perhaps overstated.

Goldstein addressed that tension, saying he’s used to nuance: “It’s complicated,” he said. “It’s not that I blame E.T. for everything. It’s that I acknowledge how formative everything is—even fictional stories.”

What emerges from his story is more than a confession, it’s an invitation. An invitation to look back at what shaped us—even the shadows we thought we left behind. To consider what scared us, and how those fears morphed. To examine how, in our adulthood, our reactions—maybe to a loud noise, to night’s darkness, to abandonment—might have roots we didn’t expect.

By the end of the interview, Goldstein seemed lighter. There was catharsis in describing what he carried. He also offered gratitude—to his parents, who listened, even if they didn’t fully understand; to therapy, for helping; and to the stories, even scary ones, because they helped him see his emotional landscape more clearly.

The tale underscores how much early experiences matter. It also shows how celebrity confessions can help others feel less alone. Whether or not E.T. truly gave him clinical PTSD, Goldstein’s honesty opens up space for talking about childhood, imagination, fear, and growth.

In a culture that sometimes dismisses fear as childish, stories like his reclaim it as human. They remind us that trauma isn’t always big headline events—sometimes it’s quiet, lingering, woven between bedtime, shadows, and a movie’s flicker on the wall. And sometimes naming what scared us is part of what helps us find peace.

News

Indiana Fever DEMOLISH Atlanta Dream in Playoff Thriller – Star Center’s Unstoppable Night Proves Too Much Despite Questionable Calls from Officials!

In a stunning and defiant display of resilience, the Indiana Fever marched into a hostile environment and delivered a resounding,…

Hallmark Icon Paula Shaw Dies at 84—Hollywood Mourns as Tributes Flood In for the Beloved Star Who Touched Millions With Her Roles and Left a Lasting Legacy of Grace, Strength, and Heartfelt Performances.

Paula Shaw, a fan favorite in Hallmark movies for her loving grandma roles, has died, has died at age 84….

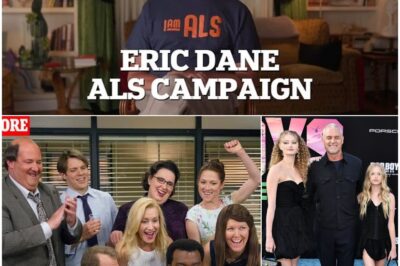

Eric Dane’s Surprise Return Stuns Fans—Reveals Emotional ALS Message After Emmy Absence Sparked Worry, Leaving Hollywood Shaken and Supporters Heartbroken Over His Powerful, Unexpected Disclosure!

Eric Dane used social media to announce a new initiative for ALS research and funding this week. The 52-year-old actor —…

’90s Icon Who Lit Up Screens in Pretty Woman Leaves Fans STUNNED—Spotted on Rare Outing Looking Totally Unrecognizable, Sparking Rumors and Shock Across Hollywood! What Happened to America’s Sweetheart?

Fans of ’90s TV and film were in for a treat when one of the decade’s most recognizable stars made…

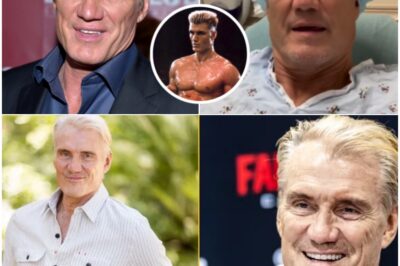

Dolph Lundgren, 67, SHOCKS the World With Cancer-Free Update—“I Feel Good,” Says the Rocky Legend, as Fans Celebrate His Incredible Recovery and Speculate on His Triumphant Return to the Big Screen!

Rocky star Dolph Lundgren shared that he is feeling ‘very well’ after beating cancer last year, adding: ‘NED, they call it. No evidence of…

Mariah the Scientist’s “Rainy Days / Burning Blue” Stops Time on The Tonight Show—Crowd Silenced, Fallon Visibly Moved, and Fans Declare It the Rawest, Realest Live Performance They’ve Ever Witnessed!

Mariah the Scientist stepped onto The Tonight Show stage carrying more than just her voice. With “Rainy Days” and “Burning…

End of content

No more pages to load

Leave a Reply