Part One: The House on Maplewood

From the street, the Carters’ split-level on Bluebonnet Drive looked like a portrait of Texas suburbia: ranch roofline, two live oaks that refused to coordinate their shade, a plastic pink scooter abandoned near the mailbox like a punctuation mark. On weekdays, the house absorbed the rhythm of Martha’s shifts at the hospital and exhaled the warmth of a seven-year-old’s laughter. On weekends—lately—the place had been an echo chamber.

“Mom, look! I drew this at school.” Amy met Martha at the door the way joy meets exhaustion: without apology. Her hair was a little wild; her socks did not agree with one another. She thrust up a crayon drawing, the waxy lines earnest in a way only first graders can manage: three stick figures—Mom, Dad, Amy—holding hands under a sky that had elected to be several blues at once.

“It’s perfect,” Martha said, meaning it, because love makes art critics generous. She taped it to the wall where the others lived, a gallery of paper optimism above the shoe bench. The new drawing ached a little more than the others.

Bill had been gone a month.

The official story lived in Martha’s phone: his mother had fallen ill near Austin; he was staying with her “for a while.” He’d said it with the gravitas of a man volunteering for sainthood. Martha had offered the obvious: “We’ll all go,” she’d said, even as her brain tabulated shifts, Amy’s school routine, the algebra of driving and caregiving. Bill had winced in that way that looks like empathy but feels like boundary. “She gets stressed,” he’d said. “The doctor wants quiet.” He’d hugged Martha and kissed Amy’s hair and promised weekends. For two Saturdays, he kept the promise. Then the promises got smaller. Then they got fuzzy.

“Mom, when is Dad coming home?” Amy asked over fish sticks later, the question delivered with the matter-of-fact cruelty of children who believe in answers. Martha smiled the way grownups learn to: with muscles and hope. “As soon as Grandma’s better,” she said. “He’s taking good care of her.”

Amy made a face. “I want to take care of her, too.”

“So do I, baby,” Martha said, and looked at her phone again. No reply to last night’s “How’s today? Need anything?” No picture of a tray on a bedside table, no photo of Bill’s mother’s hand holding a mug, no proof of life that wasn’t Bill’s voice saying “busy.”

The next day, Martha tucked her doubts into the pockets of her scrubs and did what nurses do: moved forward anyway. Twelve hours into a shift that had contained two chest pains, a seizure, a baby with a fever, and one gentleman who confused triage with theater, she sank into a cafeteria chair opposite Karen, her friend of twenty years and the hospital’s unofficial lie detector.

“So,” Karen said, unwrapping a sandwich with surgical precision, “how’s the prodigal son?”

Martha laughed because the other option was crying. “Exiled to Austin. Mom’s allegedly fragile.”

“Allegedly,” Karen repeated. “Okay. I’ll be rude so you don’t have to. Why ‘allegedly’?”

“Because we’re banned from visiting,” Martha said, and watched Karen’s eyebrows execute a silent dissertation. “Doctor’s orders.” She added air quotes because sometimes punctuation helps complete the lie.

“Doctors love visitors who do dishes,” Karen said. “If this is a real deal, there are options. Home health. Private duty. Your mom. Mine. Sisters. You. The kid. Why keep you away?”

“She says, sipping coffee like it’s a solution,” Martha muttered. Then, because the mouth knows what the brain will deny, she added: “He’s different. New phone etiquette. Jumps when it pings. Leaves the room to breathe.”

Karen’s look softened. “You could drive down,” she said gently. “As a surprise. Worst case, you look silly and get good tacos. Best case…” She let the rest trail off because good friends know when not to finish your sentence for you.

That night, Amy asked again. “When is Daddy coming back?” There’s a fatigue that belongs to hospitals, and there’s a different one that belongs to houses where the story doesn’t match the furniture. Martha pressed a kiss to Amy’s hair and heard herself say, “How about we go see him?”

Amy’s eyes went wide, the kind of joy that can redeem a day. “Really? When? Can we bring Grandma cookies?”

“Saturday,” Martha said, the word landing like a dare. “It’s a surprise. Don’t tell Dad.”

Amy nodded solemnly, as if receiving instructions from Santa. “I won’t even tell my socks,” she promised, and Martha laughed so she wouldn’t break.

In the four days between decision and departure, Martha moved like a woman with an outline: shifts traded, gifts bought. She packed the watch Bill had eyed for months and declared impractical, a tin of Carol Carter’s favorite Earl Grey, a scone recipe in Martha’s handwriting because you don’t show up at a Texan’s door without carbs. Outwardly, the errand was pure Hallmark: daughter-in-law with tea, wife with surprise, little girl with arms for Grandma. Inside, the questions stacked themselves like boxes you’d rather not open: Why no visitors? Why no details? Why shut out Amy, who had never stressed a soul in her life except Mr. Hopkinson at spring concert?

Saturday morning, the highway unrolled like a promise they hadn’t asked for. Amy sang nonsense songs to the radio and asked eight times if Austin had more birds than Houston. Martha drove and tried not to let the rearview mirror reflect the old movies in her head: Thanksgiving with Carol, the Christmas Carol insisted on hosting even as grief ducked under the table. Carol’s apple pie, according to Bill, could levitate when no one was watching. Carol, practical to a fault, had bought Martha a set of mixing bowls for a wedding gift and a lecture about not using the big one for salad because “salad needs confinement.” Carol, who now allegedly needed quiet.

The suburbs of Austin did what all suburbs do—they replicated themselves charmingly. Maplewood Street appeared, leafy and unassuming, the kind of cul-de-sac that has gossip with good hair. Martha slowed in front of Carol’s house and felt the first jolt of cognitive dissonance. The yard had never been tidy. Bill’s father had been the gardener; when he died, the lawn went to seed and the roses decided to slouch. Today, the grass was borderline smug. The roses were adversarially pruned. Someone had planted impatients along the front walk with militaristic enthusiasm. In the driveway, a small red bicycle leaned casually against the fence—Amy’s size, not Carol’s. Martha and Amy both saw it at the same time.

“Whose bike is that?” Amy asked.

“Neighbor’s?” Martha lied, badly, then parked two houses down to catch her breath.

A woman in yoga pants and authority walked a small dog past and did a double take. “Martha Carter!” she called. It was Helen, Carol’s friend from the neighborhood association who had once lectured them on recycling and then had a margarita and admitted she drove five blocks to the gym. “It’s been ages.”

Martha smiled, the way you do when history meets the present before you’re ready. “Hi, Helen. How are you?”

“Good, good,” Helen said, beaming. “Carol looks great, doesn’t she? I saw her at H-E-B last week, cart piled high. Such energy. And those kids! Bill’s little boy—so darling.” She clicked her tongue, remembering. “What a handful. The girl was shy.”

“The girl,” Martha heard herself say from underwater. “And the boy.”

“Mm-hmm,” Helen said, already pulling her dog along. “Well, give my best to Carol.” She waved and left Martha in a reality with fewer edges.

“Mom?” Amy asked, hearing the tone if not the words. “Is Grandma all better?”

“It seems so,” Martha said, organizing her face. “Let’s go say hi.”

She texted Karen—We’re here. Something’s off.—and Karen replied with the speed of a woman who keeps her phone charged for other people’s emergencies: Call me after. Don’t do it alone.

The walkway had been laid with new stones, the kind that implied a homeowner with Pinterest. Martha rang the bell and then noticed the door was ajar. Voices floated out, the careless music of people who aren’t frightened. She heard Bill’s laugh—a sound she had loved for so long she recognized its gait—and another woman’s voice, warm and young. Carol’s voice, too, effervescent and not at all fragile.

“It’s Daddy,” Amy whispered, and started forward, but Martha tightened her hand. “Wait,” she said softly. “Just a second.”

Amy tipped her chin up, puzzled, but obeyed. They peered through the inch of permission at the hinge.

Inside, sunlight poured across Carol’s living room. Bill sat on the sofa with a woman about thirty tucked comfortably against him. She had long blonde hair and the kind of face that makes strangers assume she isn’t lonely. Bill’s arm rested around her like it had come with the house. At their feet, a boy the size of Amy’s bike snapped blocks into a planet. Carol emerged from the kitchen with a tray like a hostess on a magazine cover.

“Bill, Jessica, lemonade,” she trilled. “Noah, cookies for you.”

“Yay! Thanks, Grandma.” The boy scrambled to accept his inheritance.

The word hit Martha in the sternum. Grandma. She looked at Amy just in time to see the confusion widen her eyes. “Mom—” Amy squeaked, and Martha reflexively covered her daughter’s mouth with her palm. “Shh,” she whispered, and hated herself for asking her child for silence that wasn’t hers to keep.

From inside came the easy cadence of a family that believed in its own inevitability.

“Daddy, play more,” the boy said, patting Bill’s knee. “You promised.”

“Sure, son,” Bill said, and the word son rang in Martha’s ears with all the irony of a bad joke. “But help Mom and Grandma first.”

Mom. Grandma. Son. In three nouns, the world flipped into its mirror image.

Martha did something she’d never imagined herself doing. She took out her phone, slid the camera through the door crack, and hit record. Her hands shook so much the footage looked like a nature documentary filmed by an upset raccoon, but the audio was perfect.

Carol’s voice, indulgent and triumphant: “Bill, I’m so happy you’ve found your real family. You should have left that woman years ago. I told you and told you—she wasn’t right.”

She. That woman. Martha bit her lip hard enough to taste blood.

Bill’s reply, a sigh that used to end fights and now started something worse: “I know, Mom. It’s not easy. I’m talking to a lawyer. Don’t tell Martha yet. Not until it’s settled.”

Jessica’s voice, careful. “What if she finds out? What about Amy? She’s your daughter.”

“Custody will go to Martha,” Bill said in the tone of someone giving away a chair. “I have a new family now. Noah’s enough.”

Enough. The word sat down on Martha’s heart like a stranger. She stopped the recording. The anger that arrived was so clean it felt like oxygen.

She backed away and found Amy where she’d left her, in the shadow of Carol’s manicured shrubbery, crying with dignity. “Is Daddy… is that Daddy?” Amy hiccuped. “Who are they?”

Martha knelt, wiped her daughter’s face with her sleeve, and found the part of herself that hadn’t gone missing. “We’re going to find out,” she said. “But not in there, not right now. We’re leaving.”

“But—” Amy started, and Martha touched her cheek the way you touch a book you’ve read too many times.

“Listen to me. Daddy made a very wrong choice. That’s not your fault. Not ever.” She took Amy’s hand, small and hot, and led her down the walk, past the new flowers, past the red bike leaning against a future that did not include them.

Back in the car, Martha buckled Amy in, slid into the driver’s seat, and let herself shake once, full-body, like an animal climbing out of cold water. Then she called Karen.

From a motel off the highway, the room smelling of other people’s weather, Martha laid out the facts to the friend who had already guessed the shape. “I have video,” she said, balanced on the cheap desk chair. “Audio. Faces.”

“I can’t believe it,” Karen said, and then corrected herself: “I can. I just don’t want to. Come back. Don’t be alone with this.”

“I will,” Martha said. “Tomorrow. Tonight I need to decide who I am.”

After Amy fell asleep—face squashed on motel pillow, fists unclenching—Martha stood in the bathroom under the buzzing light and looked herself in the eyes. The woman in the mirror was tired. She was also someone who had walked into a lie and walked out holding the truth by its ear.

“You are strong,” she told the mirror out loud, surprising herself by not sounding like a liar. “You will protect your daughter. You will not let a man who calls a seven-year-old optional decide what happens next.”

Her phone contacts scrolled past family and friends and landed on a name she’d saved two years earlier and never expected to need: Elizabeth Cohen, attorney-at-sanity. Martha pressed the button before courage could argue.

“Cohen Law,” said a woman whose voice could balance a tray of martinis and a lawsuit. “How can I help you?”

“This is Martha Carter,” Martha said, and the use of her name with that clarity felt like a beginning. “I need to see Elizabeth. It’s urgent.”

“Tomorrow morning,” the voice said, no hesitation. “Bring everything.”

The next day in a small downtown office that smelled like eucalyptus and resolve, Elizabeth Cohen watched the video without flinching. “That’s enough,” she said when the word enough returned to insult them. “We’ll file for divorce and for temporary orders. We’ll move this fast.”

They built a plan the way you construct emergency shelter: what to grab, what to leave, what to shore up. Martha opened a new account and moved her half of the joint funds—not theft, Elizabeth assured her, math. She took photos of birth certificates and tax returns, grabbed passports and the title to the car, made a list of what mattered and discovered it was shorter than she’d feared.

That afternoon, Martha drove to her mother’s small house on the edge of Houston, the one with plastic flamingos installed at an angle of defiance. Judith opened the door and stopped when she saw Martha’s face. “What happened?” she asked, because mothers learn to skip the preamble.

“I’ll tell you later,” Martha said, bending to hug Amy, who could smell security and leaned all the way in. “Can she stay tonight?”

“Of course,” Judith said. “Forever, if you want.”

When Amy disappeared into the kitchen to inventory Grandma’s snacks, Martha stepped back onto the porch. Elizabeth stood by the car like a woman with places to be and papers to file. She asked where Martha wanted to serve him—at work, at the house, by hand or by proxy. Martha thought of Maplewood, of roses that looked like no one had bled pruning them. “At Carol’s,” she said. “With me there.”

Two days later, they stood on Carol’s porch with a rented car and no more illusions. The door opened to Bill’s face doing algebra with surprise. “Martha—why—? You shouldn’t—”

She held up the stack of papers with Elizabeth’s crisp letterhead and the blunt edges of consequence. “We need to talk,” she said, calm like an instrument tray.

“Now’s not—my mother—” he began, and then faltered when Carol stepped into view, perfectly healthy, irritation preheated.

“What is she doing here?” Carol demanded, as if Martha were a door-to-door salesperson rather than her daughter-in-law of a decade. “Bill, get this woman out.”

“I’m Martha’s attorney,” Elizabeth said pleasantly, the way sharks smile. “That’s not how this will go.”

Jessica appeared behind them, pulling Noah close. For a second, the room contained too much gravity and nobody knew where to put their hands.

“First,” Martha said, and the word lifted like a curtain. “These are divorce papers. These are temporary orders for custody. These are the conditions under which you will see our daughter, if she wants to see you at all.” She looked at Bill and then, deliberately, at Jessica. “I know everything. I know you lied. I know you used your mother as a prop. I know you called my trust stupidity. I know you are willing to give up your daughter for convenience.”

Bill reached for the old repertoire—apology, explanation, logistics—but the old soundtrack didn’t play here. “Martha, if we talk—if I explain—”

“You had a month to explain,” she said. “You can talk to my lawyer.”

“You’ll never make it without me,” Carol said, because some people mistake prophecy for power.

“Watch me,” Martha replied, because some people know their own weight.

They left. The papers stayed.

Three months later, a different front door opened to a new life. The apartment wasn’t grand. It didn’t need to be. Amy barreled past a stack of boxes into a room painted pale pink by the world’s most determined grandmother. “Mom, look! My bed is next to the window.” Through the glass, a small park flashed a promise of swings and Saturday mornings.

“It’s perfect,” Martha said, because this time the word fit without apologizing. She set down a box labeled KITCHEN—IMPORTANT and breathed. The scent of coffee slid out of the tiny galley kitchen courtesy of Judith, who had declared herself quartermaster and morale.

“Sit,” Judith said, presenting a mug and the future. “The rest can wait.”

They would still have to learn a hundred new things. Where this school kept the pencils. How to listen for quiet panic under a child’s “fine.” How to buy only enough groceries for two. But Martha had the thing she needed most: a room she could stand in without waiting for a phone to chime with someone else’s life.

On the counter, her phone buzzed. A text from Karen: Dinner tonight. We’re bringing a lasagna the size of your mistakes.

Martha laughed, the kind that survives what it has to. “Tell them yes,” she told her mother. “Tell them always.”

Outside, traffic muttered. Inside, Amy taped a new drawing to a new wall: two stick figures and a cat who looked like a comma. Underneath, in careful seven-year-old letters, she wrote: ME + MOM.

It wasn’t a complete sentence. It didn’t have to be yet.

Part Two: The Paper Trail

The first envelope arrived by certified mail two weeks after the confrontation at Carol’s. Martha recognized Bill’s handwriting on the return address, and her hand tightened before she passed it to Elizabeth Cohen.

Elizabeth slit it open with the grace of a surgeon. “It’s his response,” she explained. “Counter-petition for divorce. He wants joint custody.”

“Joint custody?” Martha’s voice snapped. “He called Amy… optional.”

“He wants leverage,” Elizabeth said flatly. “Sometimes it’s about control, sometimes it’s about reducing child support. Don’t panic.” She slid the paper into a neat pile. “We’ve got him on tape. We’ve got the affair, the deception, and his admission he’d hand over custody. Judges don’t like fathers who treat children like luggage.”

Martha exhaled, fighting down the heat in her chest. Amy was asleep in the other room, still clinging to the pale-pink sanctuary her grandmother had painted. “How long?”

Elizabeth shrugged. “Texas family courts aren’t built for speed. Six to twelve months. But temporary orders hold until then. Amy stays with you. He can petition for visitation, but only under terms we set.”

A Father’s Visit

Bill’s lawyer filed a motion for supervised visitation. Elizabeth prepped Martha as if for surgery: what questions to expect, what not to say.

“He’ll try to look like the steady one,” Elizabeth warned. “Clean suit, remorseful eyes. Don’t let him bait you. The judge cares about Amy, not about who sounds more heartbroken.”

On the day of the hearing, Bill did exactly as predicted—navy suit, tie knotted like he’d practiced. His hair was shorter; his face carried new lines. When the judge asked if he had anything to say, he leaned into his microphone.

“Your Honor, I made mistakes,” he said. “But I’m still Amy’s father. She deserves both her parents.”

Martha clenched her fists under the table, remembering the word enough spoken over a boy with blocks. When her turn came, she kept her voice level.

“Your Honor, my husband lied about his mother’s health, maintained a second household, and told another woman that our daughter wasn’t worth keeping. I have video. I don’t say this to punish him, but to show what Amy heard when she needed her father.”

Elizabeth slid the phone across. The judge leaned forward, lips thinning as Carol’s voice filled the courtroom: You should have left that woman earlier. Bill flinched when his own voice followed: Noah is enough for me.

The gavel hit softly. “Mr. Carter, supervised visitation at the Harris County Family Center. Twice a month. Ms. Carter, full temporary custody.”

Martha walked out with her spine intact, Elizabeth at her side. Bill caught her eye once, as if waiting for her to soften. She didn’t.

Amy Learns Boundaries

The first supervised visit felt like a medical exam. A room with soft chairs, toys stacked neatly, and a counselor with a clipboard. Bill sat stiff, Amy perched on the edge of a beanbag.

“Hi, pumpkin,” Bill tried.

Amy didn’t answer. She glanced at Martha, who waited in the hall. After a long silence, Amy said, “Grandma lied.”

Bill’s face crumpled. “I—”

“And you lied,” Amy added. “You said Grandma was sick.”

Bill reached, then stopped when the counselor cleared her throat. “You’re right,” he admitted. “I lied. I was wrong. I’m sorry.”

Amy folded her arms. “You called that boy your son.”

Bill shut his eyes. “I made mistakes, Amy. But you’re my daughter. Always.”

The counselor jotted notes, but Martha didn’t need them. She could see Amy straighten a little. The wound wasn’t healed, but her daughter had found her words. Boundary, spoken out loud, at seven years old.

That night, Amy told Martha, “I don’t want to go every time. Can I say no?”

“Yes,” Martha said firmly. “You get to choose. Love isn’t homework.”

The Mother-in-Law’s Collapse

In February, Carol really did collapse. A stroke, Judith reported after a call from an old neighbor. Martha’s first instinct was bitterness, the second—professional reflex—was concern.

She visited once, more nurse than daughter-in-law. Carol lay in a rehab bed, half her words slurred.

“You,” Carol rasped when she saw her. “Why?”

“Because I’m a nurse,” Martha said. “And because Amy asked if you were okay.”

Tears leaked from Carol’s eyes. “I… wrong.”

“Yes,” Martha said. “You were.” She adjusted the woman’s pillow and walked out, lighter than she expected.

Paper Battles

The months ground on in motions and hearings. Bill’s lawyer tried to argue “parental alienation.” Elizabeth countered with the recording. Bill tried to suggest Amy was being “influenced.” Martha countered with Amy’s school counselor’s testimony: “This child is articulate and clear. Her statements about her father are her own.”

Meanwhile, Martha worked double shifts when she could, her mother helping with Amy. Every payday, she moved money into a savings account labeled FUTURE in bright Sharpie. Amy added crayon drawings of flowers to the folder that held court papers.

In May, Bill’s double life officially imploded. Jessica filed for child support for Noah, only to discover Bill’s finances were already fractured. Word traveled back to Martha in a text from Karen: Jessica dumped him. Carol’s house for sale.

Martha let out a laugh that startled Amy at the breakfast table. “What’s funny?” her daughter asked.

“Life’s sense of humor,” Martha said.

Settlement

By late summer, Bill folded. In mediation, he slouched in a chair while Elizabeth read terms. Martha signed primary custody. Bill agreed to visitation, child support, and division of assets that left him in an apartment near downtown.

“I can’t fight you anymore,” he muttered.

“You already did,” Martha said. “And lost.”

The mediator cleared his throat, but Martha wasn’t sorry.

The New Normal

By October, Martha and Amy’s apartment had lost its boxy smell of cardboard and taken on the aroma of Saturday pancakes. Judith visited weekly; Laura, Martha’s sister, took Amy to movies. Karen’s family dropped casseroles and jokes.

One evening, Amy curled up in Martha’s lap with a notebook. “Mom, can I write a new family tree?”

“Of course.”

Amy drew branches: Mom, Grandma Judith, Aunt Laura, Aunt Karen (with hearts), “Friend Family.” She left Bill on a separate branch, smaller, with a dotted line.

Martha kissed her hair. “That’s perfect.”

The Birthday

On Amy’s eighth birthday, the apartment pulsed with balloons and laughter. Kids from school sprawled on the rug, icing on their cheeks. Karen brought lasagna, Laura brought cupcakes, Judith brought balloons shaped like flamingos.

Amy blew out eight candles at once, proud. “Best birthday ever,” she announced.

From the window, Martha caught sight of a car idling at the curb. Bill, thinner now, stood outside, watching. His face carried the look of a man realizing what loss feels like when it grows permanent.

He didn’t knock. After a long moment, he turned, got in his car, and drove away.

Amy hugged Martha, sticky fingers on her cheek. “Mom, thank you.”

Martha looked around the crowded apartment: her mother, her sister, her friends, her daughter glowing. “This is family,” she said softly.

Witty, Clear Ending

Later that night, after the guests had left and Amy slept surrounded by new toys, Martha wrote in her journal:

Family isn’t built out of paperwork, or even blood. It’s built out of lasagna dropped on a Thursday, out of balloons, out of friends who pick up the phone at midnight. Bill left, but what we keep—that’s ours.

She closed the book, turned off the lamp, and whispered into the quiet apartment: “Enough.”

But this time, it meant sufficient, abundant, ours.

Part Three: The Long View

Three Years Later

By the time Amy turned eleven, the crayon drawings on Martha’s apartment wall had given way to science fair ribbons and soccer team photos. The little girl who once asked, “When is Daddy coming home?” now had a sharper vocabulary. She still loved her father, but she no longer expected him.

Martha had moved up at Houston General—charge nurse on nights, with a schedule that let her see Amy off to school most mornings. It was a different kind of tired, one that came with authority. She also learned to lean into her support system: Judith still stocked their freezer, Laura still hijacked Amy for weekends at the movies, Karen still arrived with casseroles large enough to feed the block.

And then there was Ben.

The pediatrician had started as a “park friend” but had gradually become a fixture: dinners after PTA meetings, double-family picnics, a Thanksgiving where his son Joshua and Amy invented an elaborate game involving paper pilgrim hats and Nerf darts. By year three, the kids referred to one another as “almost siblings.” The adults didn’t argue.

One Friday evening, after the kids had collapsed in front of a movie, Ben looked across the kitchen table at Martha.

“You ever think about… more?” he asked, careful.

Martha smiled, tired but honest. “More scares me. Less scares me more.”

He reached across the table, not to grab her hand but to set his palm nearby—an invitation, not an order. She let her hand rest over his. No fireworks, no cinematic swell, just two people choosing steady over spectacle.

Bill’s Last Gambit

It was almost cinematic, though, when Bill reappeared.

Martha got the call on a Tuesday afternoon: his mother, Carol, had died. Real this time. Bill asked if Amy would attend the funeral.

Amy surprised them both. “I’ll go,” she said, “but not for Grandma. For me. To say goodbye to the mess.”

So Martha drove her daughter to Austin. The house on Maplewood looked smaller, the roses unkempt again. Bill stood on the porch, older by more than three years, shoulders rounded like a man who had carried too many wrong bags.

“Amy,” he said, as she stepped out of the car.

She nodded, polite, not cold. “Hi, Dad.”

The funeral was quiet. Amy stood beside Martha, chin lifted, while Bill delivered a eulogy full of phrases about forgiveness and family that sounded rehearsed.

Afterward, Bill asked to speak privately with Martha. They stood under an oak tree, the Texas sun sharp.

“I’ve lost everything,” Bill said. “Jessica’s gone. Noah doesn’t speak to me. Mom’s gone. The house is gone. I want us back.”

Martha stared at him, amazed at his audacity. “Back? After you told another woman our daughter was… enough?”

“I was stupid. I thought—”

“You thought wrong,” Martha cut in. “You thought lies were easier than honesty. You thought comfort mattered more than commitment. You thought I was too simple to notice.”

Bill’s jaw clenched. “I’ve changed.”

“Maybe,” Martha said. “But my life has changed, too. And it’s better without you.”

She turned before he could argue. Amy slipped her hand into hers. “Ready to go home, Mom?”

“More than ready,” Martha said.

Building Forward

Life rolled on, less dramatic but richer. Amy entered middle school, discovered robotics club, and filled the apartment with whirring prototypes made from recycled soda cans. She talked openly in therapy about her father, and her therapist praised her for knowing how to define boundaries at such a young age.

Martha’s relationship with Ben deepened. They never rushed labels, but their kids had already solved it: “family dinners” were scheduled like holidays, and Saturday pancake duty rotated between apartments.

One evening, Amy watched Martha and Ben cooking side by side. “You smile different now,” she observed.

Martha blinked. “Different how?”

“Like you’re not pretending,” Amy said, then went back to soldering wires.

A Quiet Victory

The divorce decree, long since finalized, was tucked away in Martha’s filing cabinet. But her real closure came one spring afternoon when Amy brought home a new project: a family tree.

Instead of names on branches, Amy had drawn circles. One circle for Martha, one for herself, one for Grandma Judith, one for Aunt Laura. Another for Karen, with hearts around it. And, at the bottom, a dotted circle labeled: “Dad—sometimes.”

“It’s messy,” Amy said, handing it over.

“It’s perfect,” Martha said, pinning it to the fridge. “Because it’s ours.”

Witty, Clear Ending

Years later, when Amy applied to college, she wrote her admissions essay on the theme of resilience. The opening line read:

“Family isn’t who shares your last name. Family is who shows up with lasagna, who helps you paint your room pink, who listens when you finally say the hard thing out loud.”

Martha cried when she read it, then laughed at herself for crying. Amy had survived the betrayal that could have broken her, and instead, she had grown sharper, kinder, steadier.

On move-in day at the dorm, Amy hugged her mother tight. “You kept your promise, Mom. You said you’d protect me. You did.”

Martha kissed her daughter’s forehead. “And you kept yours. You grew into yourself.”

As Martha drove back down the highway, Ben’s hand warm over hers, she realized the word that had once crushed her—enough—now felt different.

Her life was enough. Her daughter was enough. Love, built on truth, was more than enough.

And for the first time in a long time, she whispered into the open Texas air: “We kept what mattered.”

News

Husband dumped his disabled wife in the forest unaware a mysterious man watched everything

Leam Morgan hated long drives. Always had. The endless ribbon of highway winding through Colorado’s pine choked wilderness made her…

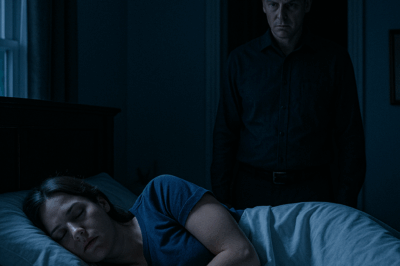

Anna began to suspect that her husband was slipping sleeping pills into her tea. That night, she discreetly discarded the drink when he left the room and acted as though she’d drifted off. But what unfolded next left her utterly stunned…

Anna suspected her husband drugged her tea, so she pretended to sleep… Anna’s heart raced as a chilling suspicion took…

During a family gathering, my grandmother inquired, «Is the $1,500 I send you each month sufficient?» I responded..

At A Family Dinner, Grandma Asked Me: «Is The $1,500 I Send You Monthly Enough?» Everyone Looked…ʼ My name is…

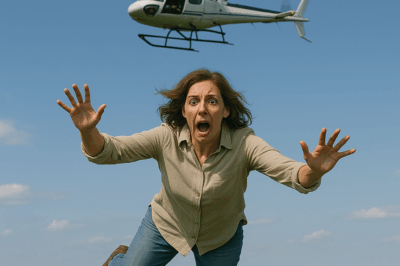

A cruel husband shoved his wife out of a helicopter for a hefty insurance payout — and her response left everyone utterly shocked

Abusive Husband Pushed His Wife From a Helicopter for Insurance Money — She Survived and Make … The wind screamed…

The poor black girl pays for a ragged man’s bus fare, unaware who is he in real…

The Poor Black Girl Pays for a Ragged Man’s Bus Fare, Unaware… You don’t have money, mister? I can pay…

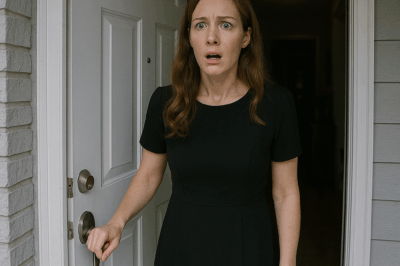

“Stay away from your husband’s funeral. Visit your sister’s house instead…” That’s the note I received on the day we laid my husband to rest. I assumed it was a cruel prank, but I went to my sister’s place anyway, since I had a key. When I pushed open the door, I was shocked by what I found…

In the morning on the day of Paul’s funeral, I received a letter. No signature, no return address. Just a…

End of content

No more pages to load

Leave a Reply